We at the Historical Awareness Research Committee have obtained and published A History of the Sado Mines in Two Volumes, a primary source document edited by Hirai Eiichi, which shows that the Sado Island gold and silver mines were not the site of Korean forced labor.

Compiled in 1950, this document is a hitherto unpublished manuscript in which Hirai Eiichi, a former mining section chief at the Sado Mines who managed its mining plants, summarized the history of the Sado Mines across two volumes spanning from the Edo to the Showa period at the request of the president of Mitsubishi Metals.

Although both a manuscript and a facsimile for this historical document exist, it is only now that the work is finally being released to the public. On January 26, 2022, the Historical Awareness Research Committee obtained the table of contents and a photograph of “Article 9: The Circumstances of Korean Laborers” on pages 844-846 of the manuscript and published them on the Committee homepage.

However, the Foundation for Victims of Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan, a South Korean government agency that is conducting field surveys and research in a bid to prevent the registration of the Sado Mines as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site, received this document from “an anonymous Japanese researcher” earlier this year on January 14.

This researcher reportedly obtained it in August 2015 from the World Heritage Registration Promotion Office in the Cultural Affairs Department of the Education Bureau of Niigata Prefecture. (This is according to the paper “New Material: Hirai Eiichi’s A History of the Sado Mines” by Jeong Hye-Gyeong (ARGO Institute for Research in Humanities), recorded in the reference material of the aforementioned foundation’s January 27 webinar titled “How Japan’s World Heritage Registration Distorts the History of Forced Labor at the Sado Mines”).

Written utilizing internal documents from the Sado mining plants, A History of the Sado Mines discloses previously unknown data on the total number of Koreans mobilized every year as well as the number that remained at the end of the war as follows.

“We recruited a total of 1,519 workers from Korea to come and work at the mines: 98 in February 1940, 248 in May, 300 in December,280 in 1941, 79 in 1942, 263 in 1944, and 251 in 1945. Of these 1,519 workers, 1,096 were immediately repatriated following the end of the war. ”

In addition, as briefly summarized below, not only was the treatment of these Korean laborers the same as that of domestic Japanese workers, but management took great care in treating the laborers well, such as by providing them with lodgings and meals.

・ Wages were equal to those of domestic Japanese laborers.

・ Payment was calculated based on output.

・ Twice-yearly bonuses for diligence, as well as bonuses for attendance, were provided based on performance.

・ Free company housing was provided for those with family, as well as low prices for daily necessities such as rice, miso, and soy sauce.

・ For those who were single, the dormitory, utilities, and bathhouses were provided free of charge, meals were provided for \0.5 JPY per day (with the company paying the difference between actual cost for meals and price charged to laborers), and vegetables were supplied from a farm directly managed by the company.

・ Each laborer was enrolled in a life insurance plan with premiums paid in full by the company.

・ Movie screenings, lectures, excursions, and sporting events were organized.

・ Magazines, Korean shogi boards, gramophones, and radios were placed in the dormitories.

(p.844)

Article 9: The Circumstances of Korean Laborers

As the number of miners drafted into the army increased with the escalation of the Second Sino-Japanese War, it became increasingly difficult to meet target increases in output.

(p.845)

Since it had become impossible to recruit within Japan, we hired a total of 1,519 workers from Korea to come and work at the mines: 98 in February 1940, 248 in May, 300 in December, 280 in 1941, 79 in 1942, 263 in 1944, and 251 in 1945. Of these 1,519 workers, 1,096 were immediately repatriated following the end of the war. There was no discrimination between Koreans and domestic Japanese workers in terms of how they were treated in the workplace, the wage system, or incentive schemes. They were employed primarily as pit workers and paid based on a piece-rate system according to how much they mined. A bonus for work attendance was awarded once a month based on days worked, rice was supplied according to the number of family dependents and the number of days worked, and a bonus for diligence was granted twice a year. For those with families, company housing was provided free of charge, there were communal baths, rice, miso, soy sauce, and other daily necessities could be purchased inexpensively through the company store, and medical examinations were conducted for sick or injured family members. Those who were single were permitted to stay in one of the three dormitories for free. Meals were the same as for the Japanese, the daily cost of which was \0.5 JPY with any difference in the actual cost being borne by the company. Bedding was rented out for \0.5 JPY per set per month, while utility costs and bathhouse fees were covered by the company. Other daily necessities such as work supplies, clothes, and footwear were also sold cheaply through the company store. Whenever there was a shortage of vegetables, stocks were replenished from a farm under the direct management of the mines. A workers association was organized in which all employees were registered; through this association, we aimed to improve employee relations, training, aid, their environment, efficiency, and welfare. We also endeavored to improve workers’ comfort and entertainment: the association held festivals and events such as movie screenings, lectures, excursions, and sporting events, and each dormitory had a recreation room with magazines, Korean shogi boards, gramophones, and radios.

(p.846)

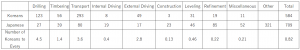

In addition, those who had been working for more than three months were enrolled in group life insurance, with the company paying for the insurance premiums of all enrollees. In the unlikely event of death, a death benefit of \300 JPY was provided, and there was no distinction between Japanese and Koreans in terms of disaster relief, or salary in the case of retirement. When they first arrived, each worker typically consumed about 1.5 kilos of rice a day; we gradually reduced portions, and there were no second helpings once rice rations were distributed. During rice shortages the fare was supplemented with sweet potatoes, radishes, or dried noodles. Both the number of personnel by occupation and the ratio of Korean to Japanese laborers in May 1943 are as indicated in the table below.

Koreans made up the great majority of the labor force in 1944 and 1945 as the number of Korean laborers increased by 514. Overall, as can be seen in the good results obtained through training and guidance, Korean laborers could be repatriated without the riots seen in other regions at the end of the war.